Originally posted March 21, 2020

Let's take a look at a tiny revolver.

Here we have a bit of an oddity from Europe, which needs some background to make any sense. In 1868, the firm of P. Webley & Son (Birmingham, England), well-known manufacturers of revolvers since 1854, introduced its first double-action model, a large, solid-frame five-shot revolver (in contrast to the company's later, and more famous, top-break models) chambered for the .442 Webley black-powder cartridge. Having been adopted as the standard handgun of the Royal Irish Constabulary (the police force of Ireland, which was then not-altogether-willingly part of the UK), this became popularly known as the Webley RIC revolver. In addition to the standard .442 model, RIC revolvers were also available for a range of other large-bore cartridges of the day, up to and including a monumental specimen called .500 Tranter Centrefire.

Four years later, Webley introduced a scaled-down pocket version of the basic RIC design, the British Bull Dog. This, despite its smaller size, was also originally chambered for .442 Webley. A bit later, Webley began offering further-scaled-down versions of the same design in more realistic pocket-revolver loadings, such as the British .320 and .380 revolver cartridges (not to be confused with any other .32-caliber revolver cartridge or the much later .380 Auto).

All of Webley's designs of the period were popular, but fairly pricey, so another thing they have in common is that they were all copied fairly extensively outside the UK. Belgian gunmakers, in particular, offered knockoffs of Webley's pocket revolvers in a wide range of different loadings. The gun we see here is one of those.

This revolver is almost completely unmarked. There is no manufacturer's name, no serial number, not even a stamp to indicate what cartridge it requires.

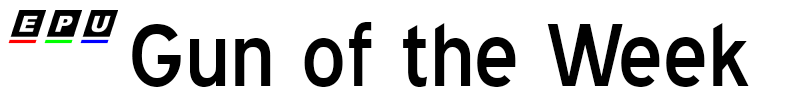

The only marking anywhere on it are the various proof stamps required by Belgian law, starting with the small group on the upper right side of the frame, at the base of the barrel.

According to a 1978 article from Gun Digest, multiple references to which online are about the only thing I can come up with on the subject, the "crown R" proof was introduced for rifled black-powder revolver barrels in 1894. The "star B" mark below it is an inspector's mark.

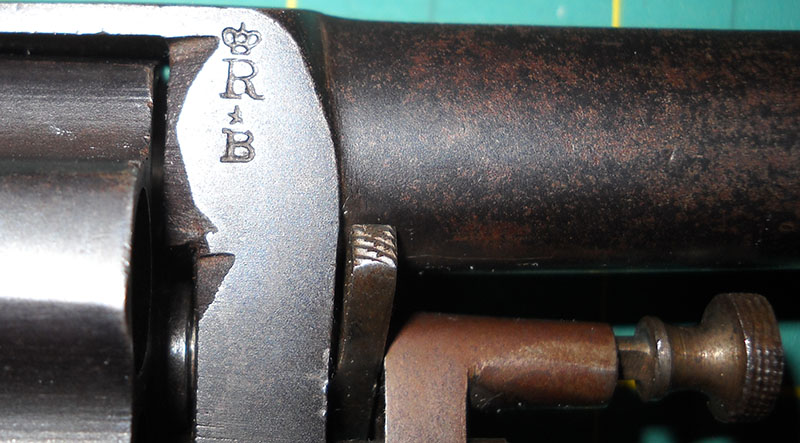

In addition to these, there are stamps on three of the webs between the cylinder's six chambers. Getting pictures of these one-handed was a bit tricky, but with a little fiddling in Photoshop I was able to make them reasonably clear. This is the first one:

This one's small and was particularly hard to see, but it's a crown over an oval cartouche with a tiny E, L, and G in it. This is the stamp of the Liège proof house (Epreuve de Liège) post-1893, and shows that the firearm received its final approval.

On the next chamber web, there's this one:

That's a crown over a C; I haven't found a definitive explanation for this one, but I suspect the C stands for cylindre, in the same way that the R is for rayé (rifled). I've also seen that this mark was used by a Swedish proof house, but that seems unlikely to be relevant to this example.

And finally, on the next web along:

The inspector's mark again. These were (and I believe still are) assigned to individual inspectors at the Liège proof house, so the letter under the star can be anything.

There's no manufacturer's roll stamp hiding up on the top, like on the Franco-Spanish Mystery, either; just the shallow top-strap groove that typically served small revolvers of this period as a rear sight notch. The front sight is reasonably substantial for a gun of this type, though.

Whoever made this revolver, he (or possibly she, but given the place and time, probably he) preferred to remain anonymous. This was not all that unusual for the Belgian gunsmith scene at the time; like Eibar in Spain, the greater Liège area had a great multitude of small factories (sometimes the use of that word stretches the reality more than a little) producing firearms more or less to order. It's as likely to find a Belgian revolver from this period marked only with the name of the shop that sold it as the factory that made it, or, as we see in this case, nothing at all.

I noted above that this revolver has no mark of any kind to indicate its caliber, let alone what specific cartridge it takes. My eyeball guess is that it has a .38-caliber bore or thereabouts, which suggests it was probably meant for the British .380 Revolver or .380 Rook, now-long-obsolete black powder cartridges that were superseded by .38 Smith & Wesson (the forerunner to today's .38 Special and .357 Magnum).

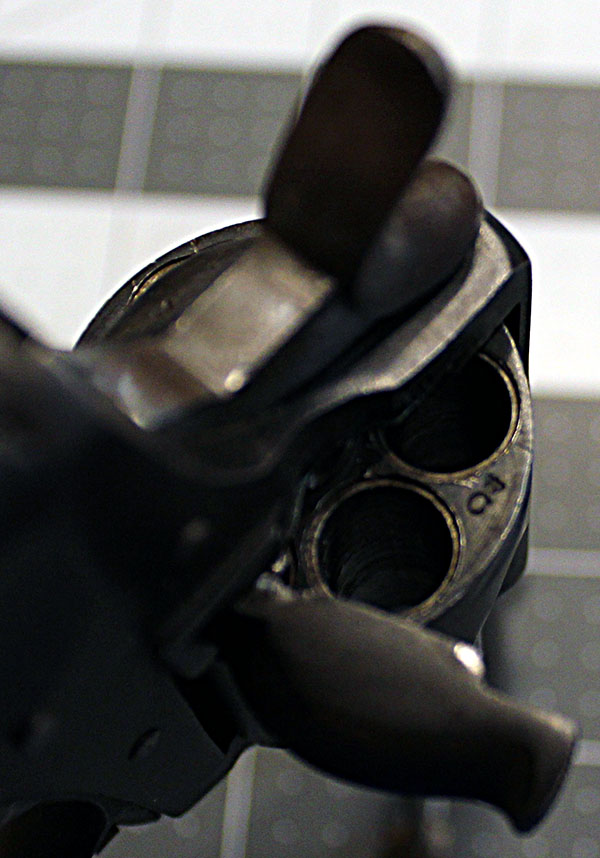

Despite being double-action, the Webley solid-frame revolvers and their various foreign progeny were gate-loaded, which was still the fashion when they were developed.

It's clear from this picture that whatever cartridge this takes, it's rimmed, which isn't surprising for a 19th-century revolver.

Ejection is, as with most gate-loading revolvers, accomplished with a built-in ejection rod. In the Bull Dog's case, this is normally stowed concentric to the cylinder axis pin, and must be pulled out and swung sideways to employ.

It is not spring-loaded, and indeed this particular one is quite worn; it won't stay in place if the revolver is held with the muzzle down, but will slide forward and flop around (though it has a slight crimp at the rear end so it can't quite fall out of the sleeve it runs in). Part of the problem there is that the screw holding the ejection rod pivot in place is loose, and if tightened, just works its way loose again when the pivot is moved. This revolver probably being from sometime in the late 1890s, that's not all that surprising. What's more surprising is that the lockup is tight and the cylinder seems still to be in good timing. On the other hand, these were vest pocket defensive guns and so generally didn't tend to be actually shot very often.

Although double-action, the Bull Dog and its copies have generously proportioned hammers for pocket guns, and will work in single-action mode.

Clearly visible here is the old-fashioned fixed firing pin, which just goes through that hole in the rear of the frame and strikes the cartridge primer directly. The gun does have a rebounding hammer, so it would be at least nominally safe to carry with all six chambers loaded. The cylinder only locks up when the hammer is cocked; it's free to rotate at any other time (and in either direction, to boot). When being indexed by the lockwork, it turns clockwise (from the shooter's perspective), as pretty much all right-side-loading gate revolvers do.

That's about all we can learn from our specific subject today, so we'll close out on a historical note. The original .442-caliber British Bull Dog's principal claim to fame, aside from the fact that George Armstrong Custer may or may not have died with one in his hand, is that one was used to assassinate a United States President. In 1881, a deranged and disappointed office seeker named Charles Guiteau, who had somehow gotten it into his head that he was President James A. Garfield's personal friend and had been promised a cushy government job if Garfield were elected (he wasn't and he hadn't; Garfield had likely never heard of him), bought himself a Bull Dog and a box of ammunition, did a little practice shooting, and then went and shot the president.

There are two ironies to the story of Charles Guiteau and James Garfield. One is that Garfield's wound was not life-threatening; what killed him, two and a half months after he was shot, was his doctors poking their unwashed fingers in there, trying to fish the bullet out. Guiteau was hanged for it anyway, of course.

One of the reasons Guiteau's insanity defense failed (apart from the fact that insanity itself was not, generally speaking, understood in a criminal justice context in 1882) was the fact, which emerged during his trial, that he had considered buying a fancier version of the Bull Dog revolver because he reckoned the one with the ivory grips would look nicer in a museum after he'd killed the president with it. This was pretty clear evidence of premeditation. (Guiteau also sabotaged his own defense by insisting that he wasn't insane, he was on a mission from God, which didn't fly with an 1882 jury any better than it would today.)

Which brings us to the other irony in the case of Charles J. Guiteau: his revolver did go to a museum (the Smithsonian Institution)... but was subsequently either lost or stolen, disappearing from the museum's collection.

And that about wraps up the story of the British Bull Dog. As black-powder firearms went out of style in the early 20th century, production of the genuine Bull Dog and its various imitators ceased. Webley chose to pursue instead the development of its break-top military revolvers, which culminated in the .455-caliber Mark VI of World War I vintage and its World War II successor, the .38-caliber Mark IV, and the solid-frame, gate-loading designs faded into history.

Next time: another tiny revolver!