Originally posted January 18, 2016

This week, let's take a look at a nice gun that has some problems.

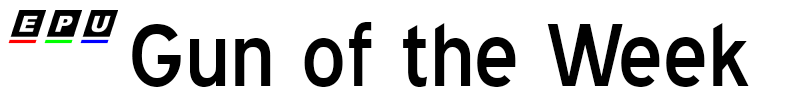

What we have here is—well, I'll let the rifle tell you itself:

Slightly hard to read thanks to the iffy photographic conditions (I really need to get or build a lightbox), but that's the lettering from the top of the barrel, and it says,

The Stevens company, under its various names, has an interesting history. It was founded in 1864, so toward the end of the Civil War, by one Joshua Stevens, who had previously been one of the founders of the Massachusetts Arms Company. (His partners in that earlier company were a couple of other mid-century gunsmiths you may have heard of, Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson.)

It's slightly hard to imagine nowadays, but Massachusetts and Connecticut used to be the heart of the American firearms industry. Chicopee Falls is not far from Springfield, where both the U.S. government's Springfield Armory and, well, Smith & Wesson were located (and S&W's corporate headquarters still resides). Colt's Manufacturing Co. was (and its headquarters remains, for however long the company manages to survive) in nearby Hartford, CT. Eli Whitney invented the great American entrepreneurial pastime of bilking the {War|Defense} Department in New Haven, which was later the home of Henry and then Winchester Repeating Arms. Sturm, Ruger & Co. (about whom more in a later installment) was founded in Southport. And so it goes. Nowadays, there are still some corporate offices in the region, but manufacturing is almost exclusively done elsewhere.

At any rate, the J. Stevens Arms and Tool Company, which eventually dropped the "and Tool" from its trade name, entered the market with a tip-up pistol and moved from there into repeating rifles and whatnot. The original Stevens Tip-Up eventually evolved into a model variously called the No. 35 and the Favorite. You may remember that name from an earlier Gun of the Week. In 1916, the Stevens works was bought out by a newly created division of Westinghouse, the electrical equipment company, which had just won a contract to build scads and scads of Mosin-Nagant rifles for the armies of Russian Tsar Nicholas II.

We've seen how that story ended—Nicholas ceased to be tsar within a year (and ceased to be alive within two), and his replacements declined to honor the contract. After a bailout from the U.S. government, Westinghouse then got back out of the gun business and sold the Stevens plant to Savage Arms, a company with what might be the most unfortunate name in American industry. (It's actually named after its founder, Arthur Savage, but, well... yeah. They even used a stylized Indian head, like used to be on U.S. 5¢ coins, as their logo. It was the 1890s. What can you do.) Savage is still in business today and still sells products under the Stevens name.

The Visible Loading Repeater, commonly (and eventually officially) shortened to Visible Loader, was introduced in 1908, and products based on its action were in production through 1934. (This type, which was known in the catalog as the Model 70 or No. 70, was replaced in 1931 by a slightly different version, the No. 71, but the action was the same.) It's impossible to date them with much certainty thanks to both the loss of the company's records from before World War II and the fact that—puzzlingly—they repeated serial numbers, but from this one's markings we can work out that it was made sometime between 1920 and 1925-ish.

We know it's from before around 1925 because the markings on top still say "Visible Loading Repeater"; this was changed to Visible Loader a little while after the Savage takeover. Nobody seems to know exactly when, but the usual best guess is circa 1925. We know it's from 1920 or later because that's when the Savage takeover happened, and the left side of the receiver has a rather tasteful SVG cartouche:

That's right: The gun says Stevens on it in two separate places, the top markings we've already seen and a banner on the righthand side of the barrel base:

But it doesn't say "Savage" anywhere on it. Just that understated little monogram. This was the only visible indication of the takeover in the early days. Imagine a modern manufacturer buying out one of its competitors and leaving its branding alone as completely as that.

Anyway! Onward to mechanical considerations. The No. 70 is a pump-action .22 rimfire rifle with a single-action trigger. As the markings on the left side of the barrel show, it can (like the Favorite) operate with .22 Short, .22 Long, or .22 Long Rifle:

One interesting thing about the No. 70 is that even though it's a repeater, it doesn't care what combination of those cartridges you use. If you have a couple of .22 Shorts, a few Longs, and a Long Rifle or two, you can load them all indiscriminately. The action operates in a distance that will accommodate the longest of the three (Long Rifle), but not so long that the shortest (Short) won't also work, and since they're all low-pressure rimmed cartridges, the length of the actual chamber doesn't matter much.

Speaking of which, let's get a closer look at that action. Here it is closed:

And open:

Note that it doesn't open very far, but then it doesn't need to, because .22 Long Rifle is not very long. Refer to this ammunition comparison from a previous episode to refresh your memory on that.

The receiver on this gun is symmetrical; there is nothing different going on over on the left side.

I didn't bother trying to conceal the serial number in this shot, because frankly it doesn't matter. There were at least four No. 70 rifles with this same serial number, because Stevens used a letter-and-three-digits serial numbering scheme, under which a total of 25,974 unique serial numbers were available (assuming each letter's block started at 001, not 000). When they hit Z999, they'd just go back to A001 and start again. Total production of the No. 70 was, as best as anyone can guess, somewhere north of 100,000, which implies that each number was used at least three and probably four times.

I should note that this was perfectly legal at the time, in a way that it would absolutely, totally not be now. Firearms manufacturers in the United States before 1968 were not required by law to give their products serial numbers at all, and those which chose to (and to be fair, most did) were under no obligation to make them unique. In Stevens's case, they only seem to have numbered their products for internal reference, and since far fewer than 25,974 rifles were ever going to be on the company's own books at any one time, the system was considered adequate. If one of these rifles were to be exported to a foreign country and then reimported to the United States, it would have to be issued a new, unique serial number by its importer, but as pre-'68 domestic production, they're grandfathered.

Getting back to the mechanics, another thing that can be seen in these shots is that, in common with many pump- and lever-action rifles from this period, the single-action hammer is mechanically cocked by being displaced by the cycling action. It can also be cocked manually, for instance to restrike a dud cartridge (though that is usually futile, it has to be said).

From above and behind, some details can be seen, including the mouth of the chamber and (at the bottom of the frame) the back of the firing pin, which is struck by the hammer to fire the round.

Another feature the No. 70 shares with many other pump and lever guns is its tubular magazine below the barrel. In this rifle's case, loading is accomplished not through a gate, as in the Winchester 94, but by partly dismantling the magazine. At the front of the tube is this knurled knob.

With that retaining nub turned out of its slot, the entire magazine follower assembly can be removed and a number of rounds (I'm uncertain how many; it varies by the length of the rounds you're using, and as noted above, you can mix and match if you like) inserted into the magazine tube by hand.

When the follower is replaced, the rounds inside the tube depress that spring-loaded plunger you can see at the end, which is the actual follower and what pushes the rounds into the action. It'll hold as much ammunition as will still leave room for the fully compressed spring inside the follower tube once you've fully meshed them back together and set the locking nub. This is a cumbersome system—nowadays designers of integral magazines at least try to make sure there isn't a vital part of the firearm that actually comes all the way off and can theoretically be lost—but then the No. 70 was never intended to be reloaded under any sort of time pressure. These were meant for shooting at tin cans on a fence somewhere, or in county fair shooting galleries (which used to be a thing), not serious field use.

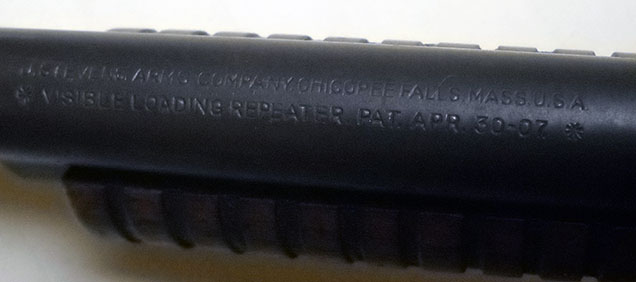

A closeup of the open action shows how this system works, and reveals why the rifle was called the Visible Loader:

Because the loading system is, in fact, fully visible inside the action. That rounded-end cylindrical bit you see at the bottom of the chamber is the magazine follower, that spring-loaded plunger visible in the dismantled-magazine photo. When the magazine is loaded, that plunger's spring pressure makes sure there's always a fresh round down there, waiting to be loaded, and then it emerges into position when the last round is chambered so that the empty doesn't fall back into the magazine when it's extracted. In operation, you can (if you position the rifle correctly) actually see the whole extraction-and-loading cycle in action.

There is no manual safety on this rifle, which seems odd to modern sensibilities, given that Stevens routinely stressed the safety of the product in advertisements. There's a fairly robust integral safety system, though, which is actually what they were talking about; it won't prevent accidental or negligent discharges, but that was considered the shooter's full responsibility back in those days. What the rifle's built-in safety system is meant to do is ensure that it can't fire in an unsafe condition, and it does that quite well. Basically, if the hammer is cocked, the breech is locked shut and the slide will not operate. This means that even if the shooter accidentally applies rearward pressure on the slide while shooting—which is fairly easy to do, since that's naturally where your supporting hand stays—the breech won't unlock and the rifle cannot fire out of battery. Once the hammer drops, it will, but by then the bullet is on its way and the chamber pressure has fallen to safe levels. This system would probably not be advisable for high-pressure cartridges,¹ but for .22 rimfire it's perfectly adequate and works well.

Unfortunately, not a lot else works really well on a Visible Loader. The design is a bit too ambitious mechanically. No. 70s worked very well when they were new and scrupulously cleaned, but dirt and wear both cause the mechanism to become finicky. As you might imagine, given that the newest Visible Loader left in the world is at least 82 years old, they're all pretty worn by this point, but even when they were younger, the shortcomings of the operating system earned them the (sometimes semi-affectionate, usually not) nickname "Miserable Loader".

Mind you, even when they were in perfect working order, they weren't perfect. They have a double extractor, for instance, so extraction is generally no problem, but there's no ejector; the next round coming up is meant to eject the empty. Sometimes that works! Sometimes it doesn't. (This is also naturally one of the features that tend to work less and less well as the rifle gets dirty. Or if the ammunition is of poor quality.) Since the follower only moves along the axis of the magazine, it obviously doesn't pop up once the last round is fired, meaning the last empty doesn't eject at all; it just sits in there until you pick it out with your fingers or turn the rifle over and shake it out. (Annoyingly, because the mechanism isn't enclosed at all, a live round can also fall out if you tip the rifle far enough at the right moment in the cycle.)

Mine also suffers from a problem fairly common to older, more worn No. 70s, in that part of the operating mechanism no longer fits or functions securely. The way the pump works in these rifles is surprisingly complex for what they are. Here's that right-side view of the receiver again:

Notice that from top to bottom there, we have the barrel, the magazine tube, a bit of the mechanism, and then at the bottom the structural rail the pump slides on. That bit in between is a little camming lever that moves in a complex way during functioning, and if it's out of position more than just a little bit, it won't slide properly and the mechanism jams. Note that since it's worn, it's often out of position more than just a little bit. Sometimes, if it's out of position in just the wrong way, it comes out altogether, rendering the whole works nonfunctional until it can be finagled back into its place. If it fell out in a grassy field or sandy area, good luck finding it again!

I bought this rifle 15 or so years back because it wasn't very expensive and I think these old slide-action .22s are cool, but to be honest, thanks to the limitations described above, I don't shoot it much. It's kind of a pain in the ass. All the same, because of my documented weakness for oddballs and underdogs, it's welcome in my cabinet.

--G.

¹ Note that there are modern "hypervelocity" .22 LR cartridges available that develop much higher pressures than would have been thought reasonable 100 years ago, and those should not be used in these old rifles, but then that's a fairly reasonable precaution to take when using any type of vintage firearm that modern "souped-up" ammunition is available for. Early .38 Special revolvers, for instance, should on no account be used to fire modern "+P" .38 Special ammunition, even though it's still marked .38 Special—the pressure it generates is too high to be safe.