Originally posted February 28, 2020

Many years ago, the old History Channel ran a series about firearms history called Tales of the Gun. Each episode opened with this solemn voiceover:

The gun has played a critical role in history: an invention which has been praised and denounced, served hero and villain alike, and carries with it moral responsibility. To understand the gun is to better understand history.

I assume, though I have no hard evidence to back it up, that the show's producers felt the need to include that message in an effort to head off the controversy that they knew putting such a program on basic cable in the '90s would attract. This was the age of the federal "assault weapons" ban in the United States, about which more later, and contemporary with the imposition of draconian firearms restrictions in the United Kingdom and Australia following mass shootings in those countries. Firearms and firearms enthusiasts were not super-popular with the channel's then-principal demographic, and any media outlet daring to air anything that might seem as if it were celebrating or glorifying same was taking a risk.

As then, so now, only arguably more so. We live in an age of shooting incidents, reactions to same, counter-reactions to the reactions, and so forth, seeming to become ever more violent at every phase. The AR-15 rifle family plays no small part in all of that, and I hesitated for a long time before undertaking this article as a consequence.

Besides which, on the face of it, the AR-15 isn't really my sort of gun. I'm not a "black rifle" guy, nor am I particularly Tactical™. I tend toward that 1870s-through-1940s gun demographic—say from the widespread adoption of the metallic cartridge through the immediate aftermath of World War II. I like my guns to have wood and chemically uncomplicated metal finishes on them.

But I got to thinking about it, particularly after I did the article about the AK family, and I realized that the AR family is not much more recent than that. It's very much part of that post-World War II realignment of values in the realm of the military service rifle, a product of lessons learned from Allied examination of captured German equipment at the end of the war. Arguably somewhat belatedly learned on the part of the United States ordnance community, it could be argued, but we'll get into that later. The point is, it's on that same continuum. And, shockingly enough, it's old—going on 70 years old if you follow the family tree all the way back. Even in its most familiar incarnation, the U.S. M16 rifle, it goes back more than fifty. Generations of American soldiers have used one form or another of the AR platform at this point.

So... I bought one. Here it is.

This is the most basic, bare-bones, "heritage-style" AR-15 I could find that was in any way close to affordable: a genuine Colt AR-15 Lightweight carbine, circa the mid-to-late 1990s. We'll take a closer look at in a minute, but first, a bit of history. The history of the AR platform is very convoluted, far beyond the scope of a simple web article like this, but I'll see if I can give you the broad strokes.

The United States armed forces came out of World War II with the same service rifle they took into it: the Rifle, Caliber .30, M1, popularly known as the M1 Garand rifle after its principal inventor. This was a large, heavy, imposing semiautomatic rifle chambered for the venerable, and quite large, .30-'06 Springfield cartridge, which was originally developed for the bolt-action Rifle, Caliber .30, M1903. Although powerful, reliable, and well-liked, the Garand was obsolescent by war's end, although it took a while for anyone to realize it.

Development of smaller, lighter, more rapid-firing rifles, with greater capacities of less extreme ammunition, was well along in a few countries other than the United States at the end of the war, and continued thereafter. The Soviet Union had already adopted an intermediate-cartridge-firing carbine, the SKS, while the war was still going on, and replaced it almost immediately thereafter with the AK-47. Germany was not allowed to develop its promising Sturmgewehr technology in the years immediately following the war, but captured examples were providing a roadmap to similar developments across much of the postwar world. Placed against those developments, the long, heavy, punishing Garand was a bit of a dinosaur.

That didn't stop American forces from taking the M1 into their next war, the so-called "police action" in Korea, in 1950. If it was good enough to whip the Krauts, it should be good enough to take on the Commies. And so it proved to be, but by the suspension of the conflict (it never really ended) in 1952, even the U.S. Army had to admit that the Garand's day was over.

And so, conveniently, was that of the .30-'06 cartridge. Advances in propellant technology and bullet design, along with a development effort that stretched, in fits and starts, all the way back to the end of World War I, had yielded the T65E5 experimental cartridge, which was smaller and lighter but ballistically more or less equivalent to its 1906 predecessor. In 1954, the T65E5 was standardized as 7.62×51mm NATO—so called because it was intended to be, and indeed became, the standard rifle cartridge to be used across the members of the postwar Western Allies' new military alliance, the North American Treaty Organization.

With a new cartridge in hand and an obsolete rifle to replace, the United States military embarked on a new round of its favorite intramural sport, rifle trials. You may recall from our M1 installment that the trials leading to that rifle were a decade-plus-long adventure in bureaucracy and infighting. Well, it should surprise no one that the ones following the adoption of 7.62 NATO were more of the same, only weirder, because it was the 1950s.

There were basically four competitors for the honor of replacing the M1. Two were versions of the T44, a Springfield Armory design that was essentially an improved M1 retooled to use the new cartridge and add the other features required by the new rifle specification (principally, selective fire capability and a detachable box magazine). Another was Fabrique Nationale of Belgium's Fusil Automatique Léger (FAL), a rifle designed starting just after World War II by Dieudonné Saive, FN's chief designer and a protégé of the late John M. Browning (you may recall it was Saive who stepped in and completed the GP35/Hi-Power's design after Le Mâitre's death in 1926).

The third was an oddball prototype submitted by a tiny, little-known, virtually-brand-new engineering firm called the ArmaLite Corporation. Little more than a nine-man idea factory operating out of a tiny machine shop, ArmaLite had two powerful hole cards. One was the backing of the Fairchild Engine and Aircraft Corporation, a major defense contractor providing everything from transport planes to avionics and instruments to subcontracted components for bigger combat aircraft. The other was the services of engineer and firearms designer Eugene Stoner.

We've already met Stoner briefly in the story of the AR-7 survival rifle and its hapless predecessor, the AR-5. Stoner was the one responsible for retooling the military AR-5 into its civilian-marketable offspring, the AR-7. The prototype rifle submitted to the trials for the Garand's replacement was another of his designs, which entered the competition under the designation AR-10.

In the eyes of the trials examiners, the AR-10 was a bizarre creation. Like all of ArmaLite's designs, it was meant to be as lightweight as possible (the clue is in the name), so it made extensive use of aluminum alloys and plastics, and contained no wood at all. Its design placed the barrel and action in a direct line with the shoulder stock, which made the recoil from firing virtually linear, so that the rifle would be as controllable as possible firing the powerful 7.62×51mm cartridge. It weighed more than a pound less than its nearest competitor—less than seven pounds without ammunition—and looked unlike anything else on Earth.

The examiners distrusted it immediately.

As it turned out, they had at least one legitimate reason to; the president of ArmaLite, one George Sullivan, had insisted that the prototype be fitted with a steel-lined aluminum barrel, which blew out in testing. On the other hand, that testing was conducted by Springfield Armory, which was one of the competitors. This is like taking a competitive exam and having your paper graded by a classmate. Springfield then sent a grumpy memo to the trials board declaring that the AR-10 was an immature design that would require at least five years of development to be adoptabled.

In fairness to Springfield, this was probably true, but it will not escape the reader's notice that the rifle chosen for adoption was their T44, which became the M14. The other rejected rifle, the FAL, went on to be adopted by the British, the Canadians, the Dutch, West Germany... basically all of NATO except the United States, and a lot of other countries besides. It is the classic mid-century Western battle rifle. And the AR-10... we'll come back to the AR-10 in a minute.

The M14 entered production in 1957 and was adopted in 1959. Within a very short time, it became clear to almost everyone involved that it was the Wrong Rifle. My grandfather, who shot competitively for the Army Reserve from the mid-1950s through the late '60s, once observed that the M14 was like they had taken an M1 and only kept the bad parts. It was big, it was heavy, it was awkward in close quarters, it fired a cartridge that was smaller than .30-'06 but still vastly more powerful than the ordinary infantryman needed, and although it was select-fire, it was virtually uncontrollable in full auto and so virtually never used that way. Springfield had attempted the always enticing but never successful "the same weapon can be a battle rifle or a light machine gun" concept, first found to be unworkable in World War I, because This Time For Sure, and, well, no, not this time either.

Also, by that point American forces were getting involved in a land war in Asia, specifically in a little place called Vietnam, where they tended to find themselves fighting in jungles. One thing you don't need in a jungle fight is a rifle that's lethal out to a thousand yards. American "advisors" in Vietnam were coming up against North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces armed with AKMs, or the Chinese equivalent, and finding that men armed with M14s couldn't put up a volume of fire to compete with them, and while men with WWII-era M2 carbines could, their cartridge was too weak to be particularly effective. This suggested that what was required was something in between the two.

Meanwhile, ArmaLite had struggled on with their rejected prototype, trying to sell the AR-10 to other armed forces abroad. They had an arrangement with a Dutch company, Artillerie Inrichtingen, to mass-produce the rifle, since ArmaLite didn't have a manufacturing base and their one attempt to make a large batch of AR-10s was a quality control fiasco. They had a few customers, most notably the Portuguese Army, but nothing like the success they had hoped for.

As such, when the U.S. Army came around soliticing candidates for a rifle trial, to be chambered for an intermediate cartridge of about .22 caliber and accurate to 500 yards, ArmaLite was on the case. Stoner and two other engineers, Bob Fremont and Jim Sullivan, set about scaling down the AR-10 and designing the requisite cartridge to go with it. These parallel efforts produced the AR-15 and the .223 Remington cartridge (later developed further into what became known as 5.56×45mm NATO). And so, we have finally arrived at the rifle we have here. Almost. It's still complicated.

Testers were very impressed with the AR-15 prototypes submitted for the new trials. They were small, handy, lightweight, and reliable, and the cartridge was ballistically everything the specification called for—and small enough that a man could operationally carry three times as much of it as he could of 7.62 NATO. The test results estimated that five men armed with AR-15s would have practical firepower equivalent to eleven carrying M14s.

Remember back in the M1 trials, when the Army Chief of Staff stepped in at the last moment and demanded that the new rifle use .30-'06, setting everything back by years? Well, it happened again. Different guy, same result: Army Chief of Staff General Maxwell Taylor read the AR-15 report, nodded, and then threw it in the trash and decreed that the Army would keep using the M14. The reports that he adopted a fake Russian accent and announced, "Nyet, rifle is fine" are apocryphal (and also don't really exist; I made that part up).

At this point ArmaLite had had enough. Presumably muttering about how you just can't please some people, they threw up their hands and sold the whole AR-10/AR-15 project to Colt.

Which is when things really started rolling, because unlike ArmaLite's, Colt's management knew how to work the military-industrial old boy network. Within a year, a Colt sales rep got a sample AR-15 into the hands of General Curtis "Bombs Away" LeMay, Air Force Vice Chief of Staff, founder of Strategic Air Command, and certified Real Piece of Work. LeMay was very impressed with the rifle and promptly ordered thousands of them. The Air Force doesn't have infantry, true, but they do have a lot of people who patrol airbase perimeters and the like, and they were getting tired of shooting people with M2 carbines and having them not die.

Meanwhile, as the Army (mostly in the person of Maxwell Taylor, who by 1961 was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) continued resisting adoption of the 5.56mm cartridge or the rifle that fired it, other forces were conspiring to get both of them into the hands of personnel in the field. ARPA, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (popularly known as the "Pentagon's Brain", the same agency which would later develop the ARPAnet, precursor to the Internet), all but smuggled a handful of AR-15s into South Vietnam and distributed them to Special Forces operators there, who loved them and clamored for more. Back home, Army marksmanship testing consistently showed that shooters using AR-15s in 5.56 scored higher than those saddled with M14s. The evidence kept mounting until it could not be ignored, even on occasions when the people doing the testing tried to rig the results to favor the M14 and 7.62.

The last straw came in 1963, when Secretary of Defense Robert "Butcher Bob" McNamara discovered that the Defense Department's suppliers couldn't build M14s fast enough to supply the spiraling demand being driven by the escalation in Vietnam. He bypassed the entire Army procurement structure and ordered that M14 production be terminated and the rifle replaced with the AR-15, which was finally, grudgingly adopted in that year as Rifle, Caliber 5.56mm, M16.

The punch line there is that, thanks to years of Army heel-dragging, the change in vendors, and some unfortunate screwing around with ammunition suppliers, the M16 was not really ready for prime time when it was adopted. The Defense Department essentially employed what would later come to be known as the Microsoft Method, beta testing by shipping the product, which is annoying when it's software on your PC, but gets people killed when it's combat rifles in a war zone. Working out the rifle's teething problems under fire was a multi-year ordeal that gave the M16 a bad reputation it took literally decades to shake off, but that's a whole different ball of wax, and I did promise you the short version what must now feel like about 15 years ago.

What's important for our purposes today is that Colt proceeded to make what I believe the young people refer to as mad bank supplying M16s to the United States military, four years after ArmaLite gave up the whole concept as a lost cause and sold it. This happened to ArmaLite depressingly often, and is why you don't see them trending on the twitters these days. Good ideas, terrible timing.

Colt also went on to produce a semiautomatic version of the AR-15 for civilian consumption, starting in 1964 and ending just last year, which is a pretty good run for a commercial firearm. (They stopped for the same reason IBM no longer sells PCs: because the civilian market is absolutely rammed full of cheaper alternatives.) There was only one gap in all that time, the decade between 1994 and 2004, when selling rifles like the AR-15 to the public was illegal in the United States.

The 1994 federal "assault weapons" ban is one of those oddities of history that leave marks for later researchers to follow and be fascinated by. Formally known as the Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act, it prohibited the manufacture for domestic sale of certain classes of weapons and accessories, and—without wishing to get too deeply into the politics of the thing—was a bit of a shambles. The problem, apart from the usual arguments over the constitutionality of restricting firearms in any way at all, was that it sought to define what an "assault weapon" was, but was written by people who didn't know much about firearms technology or usage. Its definitions therefore depended largely on what things looked like, as opposed to what they actually did or were for.

For example, the legislation defined an "assault rifle" as a rifle (based on the pre-existing definition of what a rifle is in the 1934 National Firearms Act, in essence, a shoulder-fired cartridge weapon with a rifled bore¹) that uses a detachable magazine and has at least two features from this list:

In addition, certain platforms were specifically banned by name, including Colt's AR-15.

You can probably see the problem already, which is that several of those elements are cosmetic and at least two are irrelevant to the legislation's stated aim of reducing gun crime. No mass shooter has ever, to my knowledge, undertaken a bayonet charge, and grenade launchers were already pretty effectively regulated by restricting the supply of grenades (which are destructive devices under the NFA). Pistol grips are convenient and stylish but largely immaterial to the actual performance of the firearm, especially since it took manufacturers about 11 seconds to figure out that a thumbhole stock accomplishes virtually the same ergonomics legally at the cost of only looking a bit stupid. This is why I kept putting "assault weapons" in sarcasm quotes above—not only do these definitions not match the already established ones for the same terms, they don't have any practical meaning. What the 1994 act really did was ban military-looking guns, which was annoying for law-abiding shooters and collectors, but presumably of no consequence at all to anyone who had already taken the decision to shoot up the local Dunkin'.

As an aside, possibly the weirdest restriction is the threaded muzzle one, since flash hiders and suppressors are both operator safety devices, so that is explicitly an attempt to legislate shooters into hurting themselves. (This presumably ties in with the puzzling fact that suppressors are regulated under the NFA despite having no aggressive usefulness outside of spy movies.) For whatever reason, that kind of backhanded legislation really gets my goat.

The one potentially practical bit of language in the bill restricted detachable magazines to a capacity of 10 rounds or fewer—although, once again, the data suggest that it did not achieve the intended practical effect, only the more peripheral (but I suspect no less deliberate) one of inconveniencing and irritating legitimate shooters.

It's also worth keeping in mind that only new production for domestic sale was prohibited by this law. Existing hardware, of which there was a lot, remained, and items not in compliance could still be made if they were to be sold outside the United States. Apart from causing a bit of a market panic when it was announced, a manufacturing glut just before it took effect, and a lot of irritation and new paperwork, it accomplished little of value in its 10 years in force, and was not renewed when it expired in 2004.

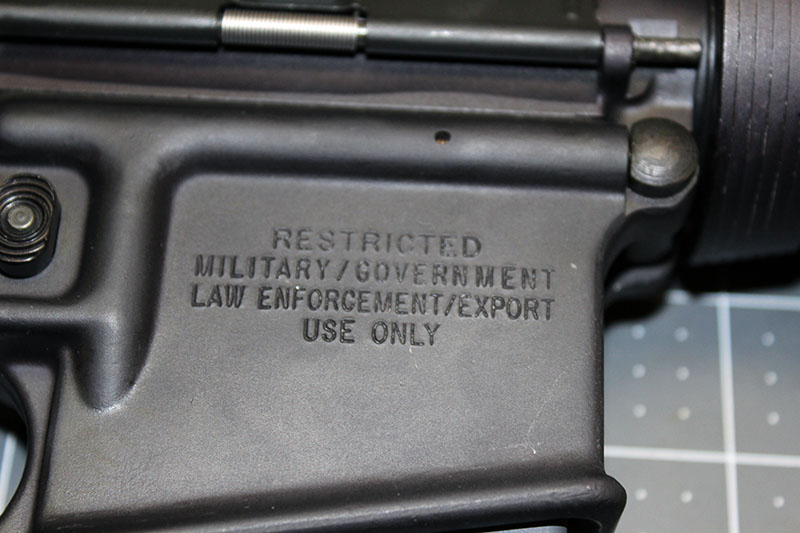

At any rate, those 10 years saw the development of all sorts of mutant guns as various manufacturers kitbashed their way around the law. Colt didn't have that option with the AR-15, since the Act specifically called them out by name. Instead, they kept it in production just as it had been before, with all of its military-style features intact, but only sold it a) outside the US or b) to law enforcement agencies, which were exempted.

I mention all this here because the specific rifle we're (finally!) about to look at was manufactured during this period. It has all of its bits, for reasons which will become obvious presently.

We already saw the left side of the rifle at the beginning, but that was ages ago, so here it is again, followed by a view of the right side.

Taking a closer look at the markings on the left side...

... we can see that this is a Colt AR-15 Lightweight™. This is a name Colt has used for numerous models over the AR-15's 56-year history as a commercial product. Generally it means it has a shorter and slimmer barrel than the regular full-size version. Identification of these rifles is complicated by the fact that there have been dozens and dozens of sub-models over the decades, each with its own unique stock number, but they aren't marked anywhere on the rifle, so you have to sort of dig up a list and play "feature bingo" to figure out which one you're looking at. I believe this one is an AR6530, but, to paraphrase the physicist Enrico Fermi, if I could keep all of these designations straight I'd have become a botanist. :)

It says "CAL. .223" here, but we'll see in a minute that, technically speaking, this rifle is for 5.56×45mm NATO, which is a very slightly different cartridge from .223 Remington. This is important because the two cartridges do not completely interchange. .223 Remington will work fine in firearms designed for 5.56 NATO, but the reverse can be dangerous. (Annoyingly, a similar distinction exists between 7.62 NATO and .308 Winchester, but it's the other way around. You had one job, ordnance people. One job.)

Whatever its precise submodel designation, this AR-15 does have a short barrel. In fact, it's the legal minimum, 16 inches; anything shorter and it would have to be registered as a short-barrelled rifle under the NFA. Most manufacturers try to allow at least a half-inch for safety's sake, but Colt went straight for the minimum. I suppose they figured they didn't need to worry too much about it, given the specific market they were aiming at.

In the middle of this side of the rifle we have the bolt release, meant to be operated with the shooter's left hand. As the name suggests, this releases the bolt (from being locked back) so that it can slam forward under pressure of the recoil spring, either to pick up the first round in a freshly loaded magazine, or to close the bolt on an empty chamber.

Up at the top rear of the carrying handle is the rear sight. Note the markings reminding the user which way turning the elevation dial (just below the sight) moves the elevation adjustment. We'll see more of how this sight works later.

Note also the fire selector switch. On this AR-15, as on all the semiautomatic civilian variants, it has only SAFE and FIRE settings. On the M16, depending on variant, that same switch would have one or two other positions (some M16 variants have a burst fire and full auto setting, where others only have one or the other). It is not ambidexterous; though you can see the other end of the switch post on the right side of the rifle, there's no switch attached. It's not particularly hard for a left-handed shooter to work, though. You get used to flipping your thumb around the grip on handguns, and the positioning of this rifle safety relative to the pistol grip is similar.

(I've seen variants on this switch that turn 180 degrees, with two SAFE positions, but this one doesn't work that way.)

Finally, at the front of the receiver is the ring that retains the front handguard. In theory, this is spring-loaded so you can pull it back and release the back of the two-piece handguard from under it for removal (if, say, it got broken, or you wanted to replace it with one that has an accessory rail molded in, or whatever). In practice, it's a very stiff spring, and you'll probably need a weird spanner that looks kind of like a rogue hacksaw to work it. I don't plan on replacing my handguard anyway, so it wouldn't really matter unless I needed to get at the gas system for some reason, at which point I'd most likely have a gunsmith doing the work anyway.

Up on top of the barrel is the following mark, which tells us something interesting and specific about this rifle:

I'm not sure what the first two characters are, possibly manufacturer's markings, but the next bit is obvious enough. This barrel (which is the part that has the chamber, as well) is set up for 5.56 NATO. This is reinforced by the last item, which is the barrel's rifling twist ratio. One turn in seven inches is quite a fast twist rate—in this particular rifle, it means the bullet will have rotated around its long axis more than twice before it even exits the muzzle—and is optimized for modern military-style rounds, which use longer and heavier bullets than the earlier versions or commercial .223.

Situations like this, where the caliber marking on the side of the rifle and the barrel disagree, are relatively common in the age of modular weapons systems, even though this one came from the factory this way. When in doubt, always go with what it says on the barrel. In this case, the conflict isn't dangerous, since rifles chambered for 5.56 NATO will handle .223 safely, but the twist ratio suggests that commercial .223 ammunition with its light bullets will not be very accurate out of this rifle. Being spun too hard is bad for a projectile's accuracy, just as not being spun hard enough is.

Let's head over to the righthand side, where we can see a stamping on the magazine well that explains why Colt could make this during the '94-'04 weapons ban:

This kind of permanent marking on a gun to which it no longer applies always amuses me for some reason. A lot of World War II-era firearms, particularly M1911A1 pistols, are marked PROPERTY OF U.S. GOVERNMENT, and the markings were not removed when the pistols were sold out of inventory. Sometimes they even say NOT FOR PRIVATE SALE on them.

I don't know whether this particular rifle was ever actually sold to a military or law enforcement agency; it doesn't have any agency ownership marks on it anywhere, which such things usually do, and it doesn't appear to have seen much use. I would guess it was either bought by an agency that didn't mark its equipment (unlikely-seeming, but possible) and not issued, or remained unsold for some reason and was only released onto the general market as new-old stock after the ban expired. The place I bought it from had a batch of them, so I'm probably its first civilian owner, but didn't specify where they came from.

Taking a closer look at a couple more of the rifle's features from this side, if you scroll back to the wider photo of its right side, and you remember the Um, What The...?, you can see that it has a forward assist. A close-up of the ejection port with the bolt closed and the dust cover open will confirm:

Unlike the Um, What The...?, this rifle's forward assist actually works! At least it works as much as forward assist in a rifle ever works, which isn't very much. Those "teeth" on the bolt are engaged by the business end of the button at the back, which forces it forward against whatever resistant might be preventing it from closing under spring tension alone.

The reason forward assists are even a thing on rifles like this is because they have non-reciprocating charging handles. On something like an AK, where the charging handle is a chunk of metal sticking out of the side of the bolt, you can just whack it with your hand if the rifle doesn't close all the way and maybe persuade it to do so. The downside of that kind of bolt handle is that it flies back and forth with considerable vigor when the rifle is operating, and if you get your thumb in the wrong place, you can be introduced to new levels of inconvenience.

(If you want to see a truly terrifying example of a reciprocating operating handle, look up some video of someone firing an old-school Maxim machine gun or one of its many variants, such as the WWI British Vickers gun or German MG08. Big old Victorian toggle handle just a-flailing back and forth, millimeters from the gunner's knuckles. No thank you, sir, may I please have a Lewis gun instead? I promise I'll look after it ever so well.)

In a rifle like the AR-15, the charging handle is a separate piece that only engages in one direction. You can pull the bolt back with it, but only back, and the bolt cycles without involving it. On the AR-10 and the early prototype AR-15s, the charging handle was a trigger-looking thing up inside the carry handle, but in the production version of the AR-15 and all its various derivatives since, it's been a sort of T-handle at the upper back of the receiver. Here's a closer view:

It has a spring-loaded latch on the left-hand side, which just engages in that little depression on the side of the upper receiver below the rear sight. To charge the rifle, you hook the first two fingers of your hand of choice over the "lobes" on the handle and haul it back until the bolt locks open. Then you push the now disconnected handle back into place, make sure it's latched so it won't flop around, and proceed with your day (generally by putting in a magazine and then pushing the bolt release button).

The problem with that, from the U.S. Army's point of view, is that there's no way to drive the bolt forward by force. In the process of (grudgingly) accepting the M16 for service, the Army brass demanded a way to do that. Stoner had omitted such a feature from the AR-10 and AR-15 designs, because he believed they were not useful—that there was no circumstance under which a rifle would fail to close where beating on it would do any good. The Air Force concurred with that belief; their pre-M16 AR-15s didn't have them, and nobody minded.

The Army insisted, however, and Colt's engineers dutifully added it. American soldiers have been making sticky M16 bolts worse by forcing grit and gunk farther into them with their forward assists ever since.

Also visible in that close-up of the ejection port is the case deflector, which is that triangular nubbin behind the port. That prevents ejected casings from flying back behind the rifle, which they would otherwise be inclined to do, and has been appreciated by left-handed riflemen ever since its introduction on the M16A2 in the 1980s.

The dust cover is spring-loaded and opens automatically when the bolt moves backward. It must be closed manually. As its name suggests, it's just there to keep stuff from getting into the ejection port.

I didn't frame this right side close-up very well, or I'd have made it a little wider so the other side of the rear sight would be in frame. You can kind of see it there, but the important part is also visible in this shot from the back:

The rear sight is adjustable in both elevation (up and down) and windage (side to side). Elevation, as we've already seen, is the big dial underneath; windage is adjusted with the knob on the side. The sight itself has a choice of two apertures: the small peep sight, for most applications (currently deployed), and the much larger aperture, commonly called a ghost ring, which can be flipped up for close-quarters or low-light work. Ghost ring fire is much less precise, but it's better than not being able to pick up the front sight at all.

Up front, just a simple square post with a couple of little ears to keep it from getting banged against things. Nowadays optics are the new hotness on AR-pattern rifles, but the old-school iron sights still get the job done. And they don't need batteries! Result.

Out at the end of the barrel is the flash hider, one of the more oddly chosen items included on the 1994 ban's Index Doohickum Prohibitorum. This has slots in the top only, so that it doesn't force gas down and kick up a big cloud of dust when the rifle is fired near the ground; the slots at the top may help somewhat with recoil compensation, though that's not the device's primary purpose.

Just to be clear, it's called a "flash hider" because its job is to make the muzzle flash less visible to the shooter. Other people can still see it just fine, particularly in low light conditions; it's only meant to make the flash less dazzling to the person who is obliged to look straight past it in order to use the sights. I suspect it may have been included on the ban list because someone thought it was for somehow concealing the fact that the gun is in use from other people, which is entirely not the case.

While we're up front, there's one more thing to see before we head back and get into the machinery.

This is a top view of the front handguard, with the muzzle to the right. The AR-15 is a gas-operated rifle; the front sight is built on top of the gas block, where the port that taps combustion gas from the barrel is. Gas makes a right-angle turn and is fed back through the gas tube, which is that silver pipe you can see inside the handguard, to the operating system inside the upper receiver, which we'll look at in a moment.

First, though, we have to take the rifle apart. Fortunately, that's ridiculously easy. There's a pin in the lower rear corner of the receiver. Push it through from the lefthand side:

It's captive so it can't get lost, which is nice. Once it's through, the rifle hinges open at the front and you can get at all the guts.

You can leave it at that, or, if you want, the hinge at the front is also a pullable captive pin, and you can take the upper assembly completely off.

In fairness, I should have pulled the magazine before I did any of this. I don't actually own any 5.56 ammo at the moment, so there was zero danger in neglecting to do so, but it's the best practice and I should have been more diligent.

Anyway, with that confession out of the way, let's have a closer look at what we're dealing with. First, with the upper removed, we have a clear view down into the lower receiver.

Not a ton to see in here. The AR-15 is hammer-fired, like many rifles of this general type. Colt redesigned the lower in the civilian AR-15 several times over its lifespan, seeking to make it progressively harder to convert to full auto. Originally all you had to do was get hold of an M16 trigger group and drop it in; by the '90s things had gotten considerably less simple than that, but the mechanism itself is pretty straightforward.

Also, note the silver disk on the left. That is the business end of the recoil spring, which is built into the stock. If you press that little nubbin below it, which is retaining the spring and its weighted buffer in the stock, you can take it out, but I decided not to do that just to get a photo of it. The buffer is there to absorb some of the impact when the bolt gets to the back of its travel and stops, which reduces felt recoil. This, along with the lighter cartridge and the linear design of the working bits and stock, is why the AR-15 platform is easier to shoot than, for example, the AK, which doesn't have anything comparable. On the other hand, it's also why it's hard to make a folding-stock AR-pattern rifle—because there has to be somewhere for the spring to live and the back of the bolt carrier to go when it cycles. That's why you often see collapsing stocks on ARs (probably the most famous one is the one on the military M4 carbine), but rarely ones that fold completely away, whereas folding stocks are common on AKs (which have their recoil spring on top).

Meanwhile, to disassemble the upper, all you have to do is slide the bolt and carrier right out the back. You can finagle the charging handle out while you're at it, although it's not necessary for most purposes. That's it! Your AR-15 is now field stripped.

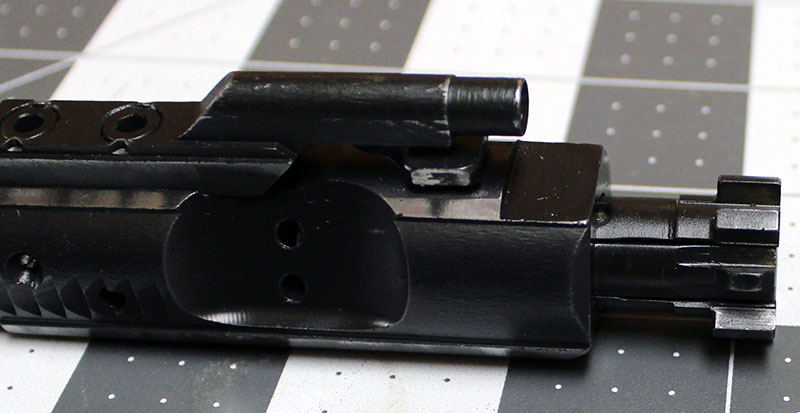

Let's take a closer look at the bolt.

Technically, in the AR-15, this is three parts. The bolt, strictly speaking, is just that bit at the front (on the right in this photo) with the locking lugs and the surface that meets the cartridge. Nearly all of the rest of that is the bolt carrier, which provides the interface between the bolt and the rest of the rifle, contains the mechanical surfaces that actuate the bolt's locking and unlocking system (in the AR's case, the bolt rotates to do these things), and provides additional mass and thereby inertia to the system.

The third bit of the equation is the gas piston, which in this system is that tiny little cylinder up on top of the bolt carrier. You may remember that in the AK system, the gas piston is an immensely long thing, much longer than the bolt carrier itself, which projects forward and meets the gas system well ahead of the action. In the AR, it's just that little piece. This leads some firearms writers to describe the AR's gas system as "direct impingement"—operating on the bolt carrier directly, without a piston—but strictly speaking, that's not quite so. It does have a gas piston. It's just very small and located behind the bolt.

Here's a closer look at both the piston and the bolt:

Sliding in and out of the front of the carrier, the bolt encounters a camming surface on the inside that forces it to rotate. It doesn't slide very far, or turn very much—just a few millimeters forward and backward, which translates to a few degrees one way or the other, just enough to engage and disengage the locking lugs.

In this view of the bolt carrier's underside (in this shot the muzzle would be to the left, sorry about that), you can see the firing pin at the back of the center section, and the cutout behind it for the hammer to travel in.

When the bolt cycles back, that angled surface in front of the firing pin is responsible for recocking the hammer.

Reassembling the rifle is almost as simple as taking it apart. The charging handle and bolt assembly take a bit of fiddling to get them to line up right (the bolt has to be forward to go in right, but sliding it into the upper makes it want to push back and turn out of alignment), but it's still the work of only a few seconds, after which you can put the front hinge back together, or just swing the rifle shut if you didn't pull that pin, slap the other pin in, and away you go.

Even to a layman like me, it's easy to see why the AR-15 platform became as popular as it did once the various teething problems that gave the early M16 such a bad name were remedied. It's a mechanically simple, reasonably elegant system, without a lot to go wrong if it's built properly in the first place and looked after. At the risk of attracting a pitchfork-toting mob, I don't see how it's terribly different from the AK system in that respect. The exact geometry, layout, and in some cases composition are different, of course, but they're both gas-operated rotating-bolt systems with the gas tube running above the barrel to an overhead piston, operated with pretty conventional trigger-and-hammer lockwork. Apart from the particulars of the gas systems, the biggest difference I can see is where they keep their recoil springs.

The M16 family remain the standard service rifles of the United States armed forces, despite repeated attempts by the U.S. Army to invent the Rifle of the Future stretching back to at least the 1980s. It's gone through a number of evolutions, of course, which have largely had to do with changes in fashion pertaining to rifle doctrine (the M16A2, for instance, introduced a burst-fire-only capability, eliminating full auto entirely, while the M16A3 reverted back to safe/semi/full and the M16A4 went back to burst again). It's also the basis for the M4 carbine, which is essentially just a shortened M16A2 (although, as once again the fashions change, the newer M4A1 drops the M16A2's burst-only mode to go back to full auto again). And the HK416 is basically an M4 with the gas system from an H&K G36, for whatever reason.

In the civilian world, there is a nigh-unto-insane profusion of AR-pattern rifles and rifles parts available. The AR-15 patents expired in 1977, so the aftermarket has had plenty of time to develop. As noted earlier, it's so lively now that it's actually driven Colt out of the civilian AR business (although they still own the trademark on the actual name "AR-15", which is why copycat rifles so often sport names in the "AR{somethingelse}" vein). People routinely build ARs completely out of third-party parts, like homemade PCs. Some companies even sell factory versions of well-regarded customs. Frankly, it's all gotten a bit out of hand. Some of these rifles aren't even visually identifiable as descendants of the AR-10 any more, so festooned have they become with rails, optics, lasers, geegaws, gimcracks, and whatchamacallits.

On a personal level, I don't regret buying the one I have. If nothing else, it's retro enough that it isn't embarrassing. (It came from out of state, and I had to pick it up at a gun shop in the area. When he opened the box to inspect the item before completing the transfer paperwork, the guy running the shop blinked and said, "Wow. That's old-school," in which I confess I took a certain perverse pride.) Besides which, viewed strictly as an engineered object, it's quite pleasant to have. It's easy to forget, now that it's been with us for 60+ years, how futuristic and weird this design must have seemed. How fragile it must have looked. It's no wonder some people resisted it.

¹ If you're curious, the exact language is "a firearm designed to be fired from the shoulder and designed to use the energy of an explosive in a fixed cartridge to fire only a single projectile through a rifled barrel for each single pull of the trigger." Note that this excludes fully automatic shoulder arms, what we would think of today as full-auto rifles and submachine guns, all of which are lumped together as "machine guns" in the NFA.)